I am a confessed fridge forager. Rescuing wrinkled tomatoes, limp carrots and saggy beets from the bottom of my crisper and making soup out of these expired edibles makes me feel resourceful. I forage to practice frugality, but mostly to procrastinate a trip to the supermarket. It’s not something I advertise about myself. Yet off late, I have heard the word foraging pop up in hip conversations and posh menus. When did foraging become such a cool thing to do?

In the urban psyche, foraging for food used to be considered a sign of poverty. But now, with the rise of the wild food trend and food walks, the urban elite are starting to view foraging not as an act of survival but as part of haute cuisine. Yet, we forget that for most of human history we have lived as foragers. It is only in the past 200 years that we have increasingly started to earn our daily bread as urban labourers and office workers. The agriculture revolution started around 10,000 years ago, but for thousands of years prior to that, our ancestors were hunter gatherers.

In our genes

Celebrated historian Yuval Noah Harari in his bestseller ‘Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind’ suggests that although the modern man lives in the city, his brain and mind still subconsciously inhabit the hunter-gatherer world, a postulation backed by evolutionary psychologists. In fact, the mystery behind why we binge on high-calorie foods is explained through the “Gorging gene theory”, a concept that proposes that the city dweller’s DNA still carries the memory of our time as foragers when food was scarce.

Harari goes on to suggest that in spite of thousands of years of evolution, we are still psychologically struggling to make the transition from forager to urbanite:

“Our eating habits, our conflicts and our sexuality are all the result of the way our hunter-gatherer minds interact with our current post-industrial environment… While this environment gives us more material resources and longer lives that those enjoyed by previous generations, it often makes us feel alienated, depressed and pressured.”

Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens : A Brief History of Humankind, Chapter 3, Pg. 45

In a bid to reconnect, not only with our natural environment but also with our intrinsic human nature, shouldn’t we be normalizing foraging? Not just in the wild and rural areas but also in the cities?

Urban foraging

Foraging is the act of looking for, identifying and picking wild or domesticated edibles for free. In the context of the urban space, it is the act of harvesting edibles from formal and informal urban greenspaces as diverse as gardens, parks, lakes, empty plots and roadsides. Interestingly, foraging is widely prevalent globally and a ubiquitous practice that has existed historically since the growth and establishment of cities (Check out this article in Sustainability).

In India, people have been traditionally foraging wild edible plants for reasons other than cooking, including its use in medicine, cultural practices like ritual bathing, warding off evil spirits and religious worship. While this practice continues to be prevalent in Indian cities, it is largely carried out by migrant workers and the economically impoverished says a 2021 study on the patterns of urban foraging in Bengaluru city by a group of researchers from the Azim Premji University. Their research reveals that 97% of the foragers are women, 81% belong to a lower social background, and 90% belong to disadvantaged communities (OBC, SC groups). The study also highlights the diversity of the plants foraged for food or medicinal purposes (76 species of flora!) and the diversity of knowledge held by these women foragers.

In a bid to dig a little deeper, I caught up with Ranjini Murali, an inter-disciplinary scientist at Azim Pemji University and the co-author of the recently published book ‘Chasing Soppu’ – a public friendly and accessible version of the academic study. She says:

“In Bengaluru, the foragers are mainly middle-aged or older women from low-income backgrounds. They are vital knowledge holders and experts on the local wild plants around them. They know what parts of the plants are used for food, medicine, or cultural uses, and which is the best season to forage. They also have delicious recipes that have been passed down through the generations”

Ranjini Murali, Azim Premji University

Anecdotal evidence suggests that growing interest in urban foraging among the elite class in Indian cities is a recent phenomenon triggered by several factors including the pandemic-induced slow down, spending more time outdoors, the rise of home gardening and other related hobbies and not to say the least, social media.

Self-taught herbalist and Founder of the popular Instagram account Forgotten Greens, Shruti Tharayil, looks at urban foraging as a way to break away from the idea that nature is “something that is out there in a forest” and as a practice to engage with the immediate ecosystem in the city. She also advocates foraging as a way to build a more resilient, local and seasonal food system, less dependent on the supermarket culture.

Foraging is indigenous, decolonized knowledge. Why do we need to eat kale, parsley and cilantro? I don’t want to demonize this, but a lot of effort, capital and energy goes into growing these exotic plants. Instead, why don’t we just look for something that is similar to kale that grows naturally in our own ecosystem?”

Shruthi Tharayil, Forgotten Greens

As Indian urbanites starting to re-engage with nature and recognize the diversity around them through the rediscovery of the art of foraging, there are also sporadic instances of newbie foragers trendifying the practice and sharing misinformation. Tharayil links this to the inclination to exotify for the purpose of content creation:

“Foraging has always been there. People from lower income communities or people who have migrated from rural to urban places have always forged in cities. It’s just that the upper middle class and upper-class people are picking it up now, making Instagram reels, talking about it and making it a thing. Trendification happens because it is seen as something exotic. If we just see something as local, people won’t hype it.”

On foraging responsibly

Ecological gardener, educator and Founder of Hara(me), Kush Sethi, conducts foraging tours in Lodhi Gardens in collaboration with Perch, a wine bar in Delhi, to create gourmet dishes from foraged wild edibles. Sethi defends that while “food-based experiences are mocked in every Netflix documentary” for being flippant, his focus has been on making foraging tours as academic as possible to keep the participants engaged with the subject and look at the plants with sensitivity. When questioned about over foraging, Sethi believes it is currently a non-issue in India:

“I don’t think you can over forage in urban spaces because the plants we are looking at are considered weeds and are being pulled out anyway. The only thing that can be a dispute of sorts are the avenue trees like mango, jamun and mulberry. Even still, a lot of jamun and mulberry just fall on the concrete and it doesn’t even have the chance to form soil. Urban foraging is not at that stage here where we will end up plucking so much that it will disappear.”

Kush Sethi, Hara(me)

However, Sethi like Tharayil and the few others including Malavika who is focused on mushrooms via her initiative Terra Myco, do educate groups on the ethical and sustainable practices of foraging. These include basics like not uprooting plants, leaving 50-70% behind, plucking only the tender leaves, or creative tactics like collecting mushrooms in cane baskets, allowing spores to drop during the walk.

Spaces to Forage

Unlike in the West where foraging is a mature practice allowing for storytelling-based content and conversations around sustainable practices, in India, the scene is nascent among urbanites and largely focused on wild, edible greens. But more seriously, with increasing urbanization and gentrification, the backward class who are the traditional urban foragers get less and less access.

“Foraging is a class thing. If it was me, the security will curiously ask what you are doing. If it was someone from a lower socio-economic background, they will say bhago yahaan se. Permission and access comes with how you look.” Sethi confesses.

Murali corroborates that urban foraging is not homogeneous and the excessive gate keeping of public spaces is leading to a drop in foraging and the loss of indigenous knowledge:

“It is a different conversation when we are talking about the elite who forage. Historically, urban foraging is primarily done by marginalized women from marginalized socio-economic backgrounds. But when this gate keeping happens and spaces don’t become available for people to forage, it stops and the knowledge also comes down.”

Murali also feels there is a need for social mobilization demanding spaces to grow more local plants and forgeable species. “In cities, people want better roads, more cafés. There is no open, vocal demand for natural spaces because it is not valued as much. Whereas, people should be demanding their policy makers for spaces to experience nature and forage.”

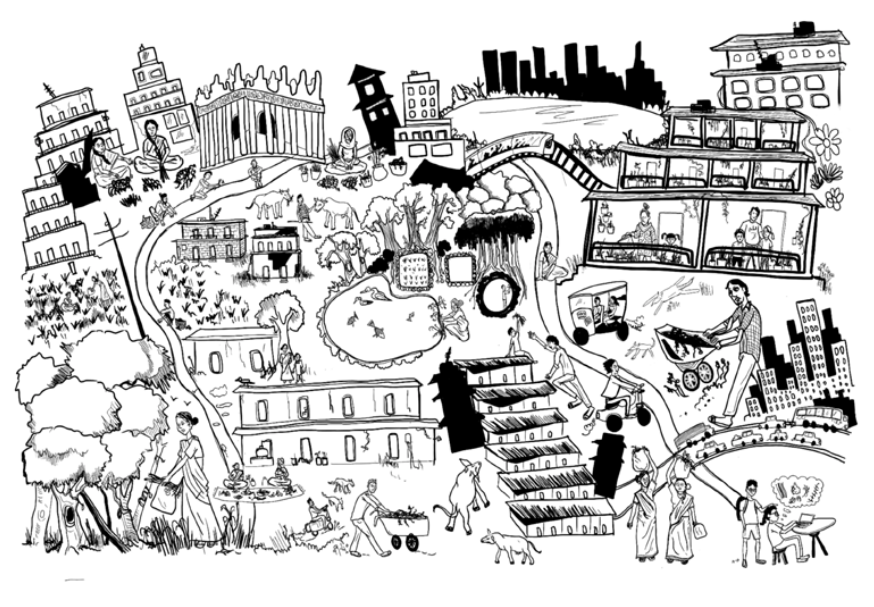

Perhaps then the conversation around urban foraging should really be about re-imagining public spaces in India, making it more accessible and equitable. To make nature within cities enjoyable, allowing local flora to flourish. But most of all, normalize foraging as a natural, human activity – just as our forager forebears did.

Postscript

In March 2023, I joined Ahmedabad University’s online course How to Write about Food led by Edible Archives, a Goa based restaurant with a vision for sustainability as a practice in the F&B industry.

This essay stemmed from the many lenses I was introduced to when thinking about food. Thanks to Culinary Consultant Swaroopa N.B, Writer Sharmila Vaidyanathan, Ranjini Murali at the Azim Pemji University, Shruti Tharayil (Forgotten Greens) and Kush Sethi at Hara(me) for being generous with their time and engaging me in conversations on the practice of foraging and rewilding.

I’m hooked for life.

Recent Comments